Hyphal knots are specialized structures formed in the mycelium of certain fungi, particularly in the genus *Armillaria*, which are crucial for nutrient storage, survival, and colonization. These knots, also known as rhizomorphs or sclerotia, are dense aggregations of fungal hyphae that develop into hardened, resilient masses, often found in soil or wood. They serve as energy reservoirs, enabling the fungus to withstand adverse environmental conditions such as drought or nutrient scarcity. Additionally, hyphal knots facilitate the long-distance spread of the fungus by acting as starting points for new mycelial growth, allowing *Armillaria* species to infect and decay trees over large areas. Their ability to persist in the environment for extended periods makes them significant in both ecological and pathological contexts, particularly in forest ecosystems where they can cause root rot diseases.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Hyphal knots are specialized structures formed by the aggregation and intertwining of fungal hyphae, often serving as anchoring points or nutrient storage sites. |

| Formation | Occur through the fusion and compaction of hyphal cells, typically in response to environmental cues or developmental signals. |

| Location | Found in various fungal species, commonly in soil, plant roots (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi), and wood-decaying fungi. |

| Function | Provide structural support, facilitate nutrient transport, and act as reservoirs for carbohydrates and other resources. |

| Morphology | Appear as dense, knot-like masses of hyphae, often darker in color due to thickened cell walls or accumulated pigments. |

| Ecological Role | Enhance fungal resilience in harsh conditions, aid in colonization of substrates, and support symbiotic relationships with plants. |

| Examples | Observed in species like Armillaria (honey fungus) and mycorrhizal fungi such as Glomus. |

| Research | Studied for their role in fungal survival, nutrient cycling, and potential applications in biotechnology and agriculture. |

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Hyphal knots are dense aggregations of fungal hyphae, often found in specific tissue regions

- Formation: They develop due to hyphal branching, fusion, and compaction in response to environmental cues

- Function: Hyphal knots enhance nutrient absorption, mechanical support, and resistance to stressors in fungi

- Location: Commonly observed in root systems, wood, and soil, where fungi colonize actively

- Significance: Studying hyphal knots aids in understanding fungal growth, ecology, and plant-microbe interactions

Definition: Hyphal knots are dense aggregations of fungal hyphae, often found in specific tissue regions

Hyphal knots, as defined, are dense aggregations of fungal hyphae, often localized in specific tissue regions. These structures are not random formations but rather strategic assemblies that serve distinct biological functions. In plants, for example, hyphal knots frequently occur at the interface between fungal mycorrhizae and plant roots, acting as nutrient exchange hubs. Here, the dense clustering of hyphae maximizes surface area, facilitating efficient transfer of minerals like phosphorus and nitrogen from the fungus to the plant. This symbiotic relationship underscores the functional significance of hyphal knots in ecosystems where nutrient availability is limited.

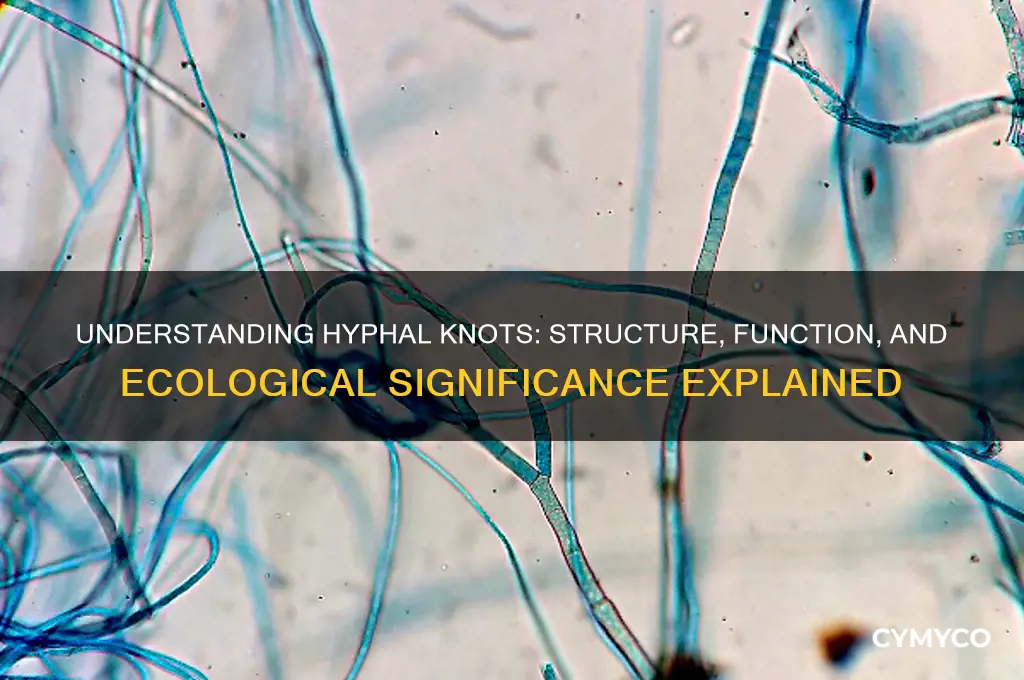

To visualize a hyphal knot, imagine a microscopic traffic roundabout where fungal filaments converge, intertwine, and thicken. This structural complexity is not merely architectural but purposeful. In wood-decaying fungi, hyphal knots form within the lignin-rich cell walls of trees, secreting enzymes that break down recalcitrant polymers. The density of these knots ensures a concentrated enzymatic assault, accelerating decomposition. For researchers studying fungal biodegradation, understanding the formation and composition of hyphal knots is critical, as it informs strategies for biofuel production or waste management.

From a practical standpoint, identifying hyphal knots in laboratory cultures requires specific techniques. Staining methods, such as Calcofluor White, highlight chitin in fungal cell walls, making knots visible under fluorescence microscopy. For field studies, tissue sampling at root-soil interfaces or decayed wood surfaces increases the likelihood of encountering these structures. A tip for researchers: focus on regions with high fungal activity, as indicated by mycelial density or discoloration, to locate knots efficiently.

Comparatively, hyphal knots in pathogenic fungi exhibit different characteristics. In infections like aspergillosis, these knots can form granulomas in lung tissue, triggering immune responses. Unlike their role in symbiosis or decomposition, here they signify disease progression. Clinicians and mycologists must differentiate between benign and pathogenic knots, as the latter may require antifungal interventions, such as itraconazole at dosages of 200–400 mg/day for adults, adjusted based on severity and patient age.

In conclusion, hyphal knots are more than just dense fungal aggregations; they are dynamic structures with context-dependent roles. Whether facilitating nutrient exchange, driving biodegradation, or contributing to pathology, their formation and function are finely tuned to environmental demands. By studying these knots, scientists unlock insights into fungal biology, with applications ranging from agriculture to medicine. For anyone exploring this topic, the key takeaway is clear: hyphal knots are not just anatomical curiosities but functional linchpins in fungal-host interactions.

Formation: They develop due to hyphal branching, fusion, and compaction in response to environmental cues

Hyphal knots are not random occurrences but structured responses to environmental pressures. These dense aggregations of fungal hyphae form through a precise sequence of branching, fusion, and compaction, each step triggered by specific cues from the surrounding ecosystem. Understanding this process reveals how fungi optimize resource allocation and structural integrity in challenging conditions.

Consider the initial phase: hyphal branching. When a fungus encounters nutrient-rich zones or physical barriers, it responds by dividing its hyphae into multiple pathways. This branching is not haphazard; it’s guided by chemical gradients, such as those of glucose or ammonium, which act as signals for growth direction. For instance, in *Aspergillus niger*, branching increases by 30-40% in the presence of 10 mM glucose, demonstrating how environmental nutrients directly influence hyphal architecture.

Fusion follows branching, as hyphae reconnect to form a network. This anastomosis, or merging, strengthens the fungal structure and allows for efficient nutrient sharing. In *Neurospora crassa*, fusion occurs within 24 hours of hyphal contact, facilitated by proteins like SO (somatic incompatibility) and HAM (hyphal anastomosis mutant). Compaction then consolidates these fused networks into knots, often triggered by physical stress like soil pressure or limited space. Studies show that compaction increases hyphal density by up to 60% in confined environments, enhancing the fungus’s ability to penetrate tough substrates.

Environmental cues dictate the timing and intensity of these processes. For example, in water-scarce conditions, *Trichoderma* species accelerate knot formation to anchor themselves in dry soil, reducing water loss. Conversely, in nutrient-poor environments, compaction slows, allowing hyphae to explore larger areas. This adaptive formation ensures fungi thrive across diverse habitats, from forest floors to human-made structures.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast. In agriculture, manipulating environmental cues like nutrient concentration or soil density can control fungal growth, either promoting beneficial mycorrhizae or suppressing pathogens. For instance, reducing nitrogen levels by 20% in soil has been shown to decrease knot formation in *Fusarium*, a common crop pathogen. Similarly, in biotechnology, understanding compaction mechanisms can improve fungal bioreactors, where dense hyphal networks enhance enzyme production. By harnessing the principles of hyphal knot formation, we can work with fungi more effectively, whether in fields, labs, or industrial settings.

Function: Hyphal knots enhance nutrient absorption, mechanical support, and resistance to stressors in fungi

Hyphal knots, often observed as swollen, compact structures along fungal hyphae, serve as multifunctional hubs critical to fungal survival and prosperity. These dense aggregations of hyphal cells are not merely anatomical curiosities but strategic adaptations that enhance nutrient absorption, provide mechanical support, and bolster resistance to environmental stressors. By concentrating cellular activity in these knots, fungi optimize resource utilization and structural integrity, ensuring their persistence in diverse and often challenging habitats.

Consider nutrient absorption: hyphal knots act as high-efficiency uptake zones, increasing the surface area available for nutrient exchange. In nutrient-poor environments, such as soil or decaying organic matter, these knots secrete enzymes more effectively, breaking down complex compounds into absorbable forms. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi with well-developed hyphal knots can increase phosphorus uptake in plants by up to 60%, a critical function for agricultural systems where nutrient availability is often limited. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this by inoculating soil with knot-rich fungal species like *Glomus intraradices* to enhance crop yields, particularly in depleted soils.

Mechanical support is another key function of hyphal knots. In fungi like mushrooms, these knots reinforce the hyphae, enabling the formation of robust structures like fruiting bodies or extensive mycelial networks. This is particularly evident in wood-decaying fungi, where knots provide the tensile strength needed to penetrate and degrade lignified tissues. For woodworkers or bioengineers, understanding this structural role could inspire the development of fungal-based composites, combining natural resilience with sustainable materials. A practical tip: when cultivating fungi for biomaterials, ensure optimal humidity (70-80%) and aeration to promote knot formation and structural integrity.

Resistance to stressors is perhaps the most adaptive function of hyphal knots. These structures act as reservoirs for glycogen and lipids, providing energy reserves during periods of drought, temperature extremes, or chemical exposure. For example, fungi exposed to heavy metals often develop larger, more numerous knots to sequester toxins and prevent cellular damage. In bioremediation projects, species like *Aspergillus niger* with pronounced hyphal knots can be deployed to clean contaminated sites, as their knots enhance tolerance to pollutants. However, caution is advised: over-reliance on knot-rich fungi in remediation may lead to toxin accumulation in the mycelium, requiring careful disposal of fungal biomass post-treatment.

In summary, hyphal knots are not just anatomical features but dynamic, multifunctional tools that underpin fungal success. By enhancing nutrient absorption, providing mechanical support, and conferring stress resistance, these structures enable fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Whether in agriculture, biomaterials, or environmental remediation, understanding and harnessing the functions of hyphal knots offers practical solutions to real-world challenges. For researchers and practitioners alike, these microscopic hubs represent a frontier of untapped potential, waiting to be explored and applied.

Location: Commonly observed in root systems, wood, and soil, where fungi colonize actively

Hyphal knots, those dense aggregations of fungal hyphae, are most frequently encountered in environments where fungi thrive: root systems, decaying wood, and soil. These locations are not coincidental. The presence of organic matter, moisture, and often symbiotic relationships with plants create ideal conditions for fungal colonization. In root systems, for example, mycorrhizal fungi form intricate networks with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake for the plant while securing a steady supply of carbohydrates for the fungus. This mutualistic relationship often results in the formation of hyphal knots, which serve as hubs for nutrient exchange and communication between the fungal and plant partners.

When examining wood, particularly in advanced stages of decay, hyphal knots become more pronounced. Here, fungi act as primary decomposers, breaking down complex lignocellulosic materials. The knots, often visible as dark, compact structures, are where the fungus concentrates its enzymatic activity. This process is crucial for nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems, as it releases trapped nutrients back into the soil. For woodworkers and foresters, recognizing these knots is essential, as they indicate the extent of fungal activity and the structural integrity of the wood.

Soil, a complex matrix of minerals, organic matter, and microorganisms, is another prime location for hyphal knots. Fungi in soil play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling, particularly in the decomposition of organic material. Hyphal knots in soil often act as reservoirs for enzymes and nutrients, facilitating the breakdown of complex compounds into forms accessible to plants. Gardeners and agronomists can benefit from understanding this phenomenon, as it highlights the importance of fungal activity in soil health. Incorporating organic matter and maintaining proper moisture levels can encourage the formation of these beneficial structures, ultimately enhancing soil fertility.

To observe hyphal knots in these environments, one can employ simple techniques. In root systems, carefully excavating around plant bases during the growing season can reveal the intricate networks of mycorrhizal fungi. For wood, cross-sectioning logs or stumps with a handsaw or chainsaw will expose the internal structures, including hyphal knots. In soil, sieving and examining the organic layer under a magnifying glass can help identify these fungal aggregations. Each of these methods provides a window into the hidden world of fungi, underscoring their critical roles in ecosystems.

In practical terms, recognizing and fostering hyphal knots can have tangible benefits. For instance, in agriculture, promoting mycorrhizal associations through specific soil amendments can improve crop yields and reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers. In forestry, understanding the role of fungi in wood decay can inform sustainable harvesting practices and pest management strategies. Even in home gardening, encouraging fungal activity through composting and mulching can lead to healthier plants and more resilient ecosystems. By focusing on these specific locations—root systems, wood, and soil—we gain insights into the dynamic and often unseen contributions of fungi to the natural world.

Significance: Studying hyphal knots aids in understanding fungal growth, ecology, and plant-microbe interactions

Hyphal knots, dense aggregations of fungal hyphae, serve as critical hubs for nutrient storage, stress resistance, and colonization in various ecosystems. These structures, often found in soil or plant tissues, are not merely passive formations but dynamic centers of fungal activity. By examining hyphal knots, researchers can decipher how fungi optimize resource allocation and adapt to environmental challenges. For instance, in *Armillaria* species, hyphal knots act as energy reservoirs, enabling the fungus to survive harsh conditions and rapidly colonize new substrates. This insight underscores the importance of studying these structures to understand fungal resilience and growth strategies.

To investigate hyphal knots effectively, researchers employ techniques such as confocal microscopy and molecular markers to visualize and quantify their formation. For example, staining hyphae with fluorescent dyes like calcofluor white allows for detailed observation of knot morphology and density. Additionally, genetic studies reveal the role of specific genes, such as those involved in cell wall remodeling, in knot development. Practical tips for lab-based studies include maintaining controlled humidity levels (e.g., 80-90%) and using nutrient-rich media to induce knot formation. These methods not only enhance our understanding of fungal biology but also provide tools for manipulating fungal behavior in agricultural or biotechnological applications.

Comparatively, hyphal knots in mycorrhizal fungi highlight their role in plant-microbe interactions. In arbuscular mycorrhizae, knots within root cortical cells facilitate nutrient exchange between the fungus and the host plant. Studies show that phosphorus uptake in plants can increase by up to 70% due to mycorrhizal associations, with hyphal knots acting as key interfaces. This symbiotic relationship demonstrates how studying these structures can inform strategies for enhancing crop productivity and soil health. For farmers, incorporating mycorrhizal inoculants into soil amendments could improve nutrient availability, particularly in phosphorus-deficient soils.

Persuasively, the ecological significance of hyphal knots extends beyond individual fungi to entire ecosystems. In forest ecosystems, hyphal knots of wood-decaying fungi like *Serpula lacrymans* contribute to nutrient cycling by breaking down lignin and cellulose. This process not only releases essential nutrients but also shapes soil structure and supports biodiversity. By studying these knots, ecologists can predict how fungal communities respond to disturbances such as deforestation or climate change. For conservationists, this knowledge is invaluable for designing restoration strategies that preserve fungal-driven ecosystem services.

In conclusion, studying hyphal knots provides a window into the intricate world of fungal growth, ecology, and plant-microbe interactions. From laboratory techniques to field applications, this research offers practical insights for agriculture, biotechnology, and conservation. By unraveling the mechanisms behind hyphal knot formation and function, scientists can harness fungal potential to address global challenges, from sustainable food production to ecosystem restoration. This focused exploration of hyphal knots not only advances our understanding of fungi but also highlights their indispensable role in shaping the natural world.

Frequently asked questions

Hyphal knots are dense, compact masses of fungal hyphae that form as a result of localized branching and intertwining of the hyphae. They are often found in certain fungi, particularly in the genus *Armillaria*, and serve as energy storage and survival structures.

Hyphal knots are typically found in the soil or on decaying wood, where they help the fungus colonize new substrates and survive adverse environmental conditions. They are commonly associated with root-rotting fungi like *Armillaria*.

Hyphal knots function as nutrient reservoirs and survival structures, allowing the fungus to persist during unfavorable conditions such as drought or nutrient scarcity. They also aid in the spread of the fungus by serving as a base for further hyphal growth and colonization.