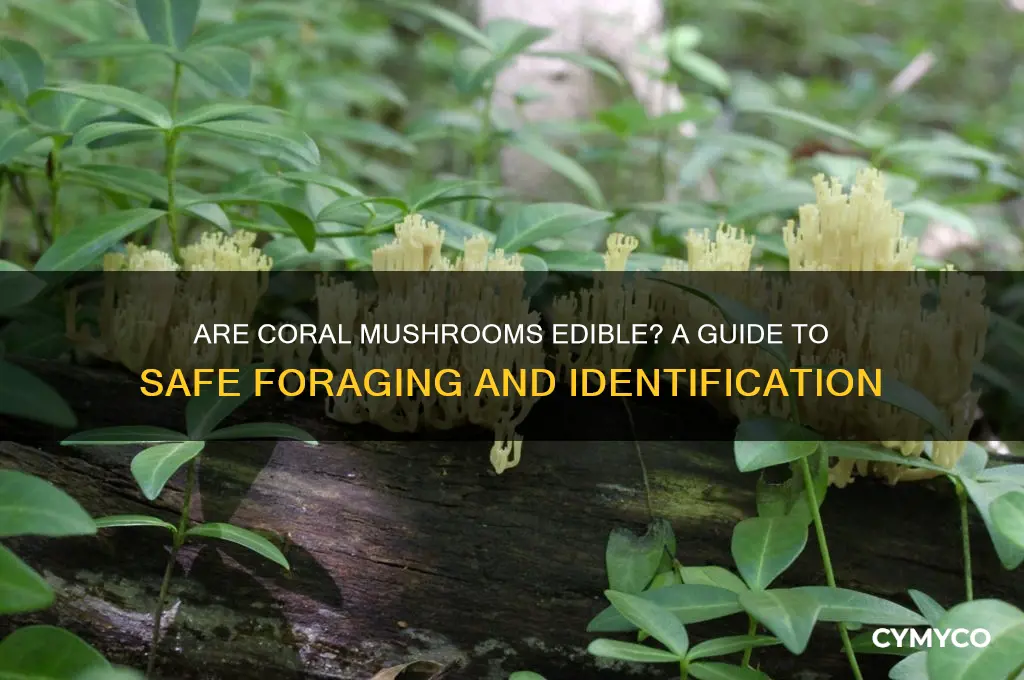

Coral mushrooms, known for their distinctive branching, finger-like structures, are a fascinating group of fungi that often capture the attention of foragers and nature enthusiasts. While some species of coral mushrooms are indeed edible and prized for their unique texture and mild flavor, others can be toxic or cause unpleasant reactions if consumed. Identifying coral mushrooms accurately is crucial, as their appearance can vary widely, and some toxic species closely resemble their edible counterparts. Popular edible varieties include the yellow coral mushroom (*Ramaria flava*) and the pink coral mushroom (*Ramaria araiospora*), but it’s essential to consult a reliable field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushroom. Always exercise caution, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Most coral mushrooms (family Clavariaceae) are considered edible, but not particularly choice. |

| Common Species | Some common edible species include Ramaria botrytis (Coral Tooth) and Ramaria flava (Yellow Coral). |

| Toxic Look-alikes | Some coral mushrooms, like Ramaria formosa (Pinkish Coral), can cause gastrointestinal upset and should be avoided. |

| Taste and Texture | Edible coral mushrooms are often described as having a mild, earthy flavor and a crunchy texture when young, becoming softer as they mature. |

| Preparation | Edible species should be thoroughly cooked to improve digestibility and reduce potential risks. |

| Identification | Proper identification is crucial, as some toxic species resemble edible ones. Consult a field guide or expert if unsure. |

| Habitat | Found in forests, often growing on wood or soil, depending on the species. |

| Season | Typically found in late summer to fall, depending on the region and species. |

| Conservation | Harvest sustainably and avoid over-collecting to preserve populations. |

| Disclaimer | Always verify edibility with a reliable source or expert before consuming any wild mushroom. |

What You'll Learn

Identifying Coral Mushrooms Safely

Coral mushrooms, with their distinctive branching structures, often captivate foragers. However, not all coral-like fungi are safe to eat. Accurate identification is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes such as the poisonous *Clavulinopsis* species or the potentially deadly *Ramaria formosa*. Always approach identification with caution and a systematic process.

Begin by examining the mushroom’s habitat. Coral mushrooms typically grow on wood or forest floors, favoring deciduous trees like oak or beech. Note the substrate—whether it’s rotting wood, leaf litter, or soil—as this can narrow down the species. For instance, *Ramaria botrytis* (the "cauliflower mushroom") often grows at the base of conifers, while *Clavaria zollingeri* (the "violet coral") prefers grassy areas. Cross-reference these details with a field guide or trusted app.

Next, focus on physical characteristics. Edible coral mushrooms, such as *Ramaria botrytis*, have a cauliflower-like appearance with thick, blunt branches that are initially white but turn yellow or brown with age. In contrast, *Ramaria formosa* starts with bright, colorful branches that fade, and it often has a sharp, unpleasant odor—a red flag for toxicity. Always smell the mushroom; a strong, unpleasant scent is a warning sign. Additionally, break a branch to check the interior color and texture; edible species usually remain consistent throughout.

Foraging alone? Carry a spore print kit. While less common, spore color can be a distinguishing factor. Edible corals typically produce yellow or cream spores, whereas some toxic species may produce white or ochre spores. However, this method is supplementary and should not replace visual identification.

Finally, when in doubt, leave it out. Even experienced foragers consult experts or local mycological societies for verification. Start with a small taste test—cook a tiny portion and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions before consuming more. Remember, misidentification can have serious consequences, so prioritize safety over curiosity.

Toxic Look-Alikes to Avoid

Coral mushrooms, with their vibrant, branching structures, often entice foragers with their striking appearance. However, not all that resembles coral is safe to eat. Among the forest floor, toxic look-alikes lurk, posing a significant risk to the unwary. One such imposter is the Ramaria formosa, commonly known as the Pinkish Coral Mushroom. While its delicate, pinkish branches may resemble edible coral species like *Ramaria botrytis*, it contains a toxin that causes severe gastrointestinal distress. Even a small bite can lead to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea within hours. Always inspect the base of the mushroom; *R. formosa* often has a more faded or yellowish hue at the bottom, a subtle but crucial detail.

Another deceptive doppelgänger is the Clavulinopsis species, often mistaken for the edible *Clavaria zollingeri* (Violet Coral). These mushrooms share a similar club-like structure, but Clavulinopsis often lacks the vibrant violet color and may appear pale or yellowish. Ingesting these can result in mild to moderate poisoning, characterized by digestive discomfort. To differentiate, examine the spore color: *Clavaria zollingeri* produces white spores, while Clavulinopsis typically produces yellow or ochre spores. A spore print test, though time-consuming, can be a lifesaver in uncertain cases.

Foraging without proper knowledge can turn a hobby into a hazard, particularly when encountering Sweating Sickener (*Dacryopinax spachiana*). This mushroom, with its orange to reddish, coral-like branches, is sometimes confused with edible coral species. However, it contains toxins that cause profuse sweating, flushing, and gastrointestinal symptoms. The key to avoidance lies in habitat observation: Sweating Sickener often grows on decaying wood, while many edible corals prefer soil. Always note the substrate when identifying mushrooms.

Lastly, the False Coral (*Xylobolus frustulatus*) is a wood-decay fungus that mimics the appearance of edible corals with its reddish-brown, branching structure. Unlike its edible counterparts, it is inedible and can cause digestive upset if consumed. Its tough, woody texture is a giveaway, as edible corals are typically more tender. When in doubt, perform a taste test by touching a small piece to your tongue; a bitter or acrid sensation is a red flag. However, this method should only supplement, not replace, thorough identification.

To safely navigate the world of coral mushrooms, adopt a meticulous approach. Always cross-reference multiple identification features, such as color, spore print, habitat, and texture. Carry a reliable field guide or consult an expert when uncertain. Remember, the forest’s beauty lies in its diversity, but not all that glimmers is gold—or edible.

Edible Species and Benefits

Among the vibrant, branching forms of coral mushrooms, several species stand out as not only edible but also prized for their culinary and potential health benefits. The Coral Tooth Mushroom (Hericium coralloides) and Sponge Coral Mushroom (Artomyces pyxidatus) are two such examples, offering a unique texture and flavor profile that can elevate dishes. These species are distinct from their toxic counterparts, such as the Ramaria formosa (False Coral), which causes gastrointestinal distress. Identifying edible coral mushrooms requires careful observation of features like color, spore print, and habitat, emphasizing the importance of foraging with an expert or using reliable guides.

From a culinary perspective, edible coral mushrooms are versatile ingredients. The Coral Tooth Mushroom, with its delicate, tooth-like spines, has a mild, seafood-like flavor that pairs well with butter, garlic, and herbs. It can be sautéed, roasted, or used in soups and stews. The Sponge Coral Mushroom, though less meaty, adds a crunchy texture and earthy taste to salads or stir-fries. To preserve their nutritional value, cook these mushrooms gently and avoid over-seasoning, as their subtle flavors can be easily overwhelmed. Incorporating them into meals not only enhances taste but also introduces bioactive compounds like polysaccharides and antioxidants.

Beyond their culinary appeal, edible coral mushrooms offer potential health benefits. Research suggests that species like Hericium coralloides contain compounds that may support immune function and reduce inflammation. For instance, beta-glucans, a type of polysaccharide found in these mushrooms, have been studied for their role in modulating the immune system. While not a substitute for medical treatment, incorporating these mushrooms into a balanced diet could contribute to overall well-being. However, it’s essential to consume them in moderation, as excessive intake of any wild mushroom can lead to digestive issues.

Foraging for edible coral mushrooms can be a rewarding activity, but it comes with risks. Always follow the rule: never eat a wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. Start by joining local mycological societies or attending foraging workshops to build your knowledge. When harvesting, use a knife to cut the mushroom at the base, leaving the mycelium intact to promote regrowth. Store fresh mushrooms in a paper bag in the refrigerator for up to three days, or dry them for longer-term use. Drying not only preserves their flavor but also concentrates their nutrients, making them a convenient pantry staple.

In conclusion, edible coral mushrooms like the Coral Tooth and Sponge Coral are not only safe to eat but also offer unique culinary experiences and potential health benefits. By approaching foraging with caution, understanding proper preparation techniques, and appreciating their nutritional value, enthusiasts can safely enjoy these fascinating fungi. Whether you’re a chef, forager, or health-conscious eater, these mushrooms are a worthy addition to your repertoire.

Proper Harvesting Techniques

Coral mushrooms, with their vibrant, branching structures, often tempt foragers with their striking appearance. However, proper harvesting techniques are crucial to ensure both safety and sustainability. Unlike common button mushrooms, coral species like *Ramaria* require careful handling to preserve their delicate forms and avoid contamination.

Step-by-Step Harvesting Guide:

- Identify with Confidence: Before harvesting, confirm the species is edible. *Ramaria botrytis* (cauliflower mushroom) is a safe choice, but *Ramaria formosa* (pinkish-white coral) is toxic. Use a field guide or consult an expert if uncertain.

- Use a Sharp Knife: Cut the mushroom at the base of the stem, leaving 1–2 cm of the stem intact. This minimizes damage to the mycelium, allowing the fungus to regenerate.

- Avoid Overharvesting: Take no more than 20–30% of the visible fruiting bodies in an area. Overharvesting can disrupt ecosystems and deplete future growth.

- Handle Gently: Place harvested mushrooms in a basket or mesh bag, not a plastic container, to allow spores to disperse and prevent moisture buildup.

Cautions and Considerations:

While coral mushrooms like *Ramaria botrytis* are edible, they can cause gastrointestinal distress if consumed in large quantities. Limit initial servings to 50–100 grams per person to test tolerance. Additionally, avoid harvesting near roadsides or industrial areas due to potential chemical contamination.

Sustainability Matters:

Proper harvesting isn’t just about safety—it’s about preserving fungal ecosystems. Mycorrhizal species, like many corals, form symbiotic relationships with trees. Disturbing their roots or overharvesting can harm both the fungus and its host. By respecting these techniques, foragers contribute to the longevity of these unique organisms.

Practical Tips for Success:

Harvest after a dry spell to ensure the mushrooms are firm and free of rot. Clean your tools with a 10% bleach solution between uses to prevent the spread of pathogens. Finally, document your harvest locations to track regrowth patterns and avoid over-foraging in the same spot.

By mastering these techniques, foragers can enjoy the culinary delights of coral mushrooms while safeguarding their natural habitats for future generations.

Cooking and Preparation Tips

Coral mushrooms, particularly the *Clavulina* species like *Clavulina coralloides* (white coral mushroom), are not only edible but also a delicate addition to culinary creations. However, their preparation requires precision to preserve their unique texture and mild flavor. Unlike heartier mushrooms, coral mushrooms are best suited for gentle cooking methods such as sautéing or blanching. Overcooking can cause them to disintegrate, so aim for 2–3 minutes in a pan over medium heat or a quick 30-second blanch in boiling water. Always pat them dry before cooking to remove excess moisture, which can dilute their subtle taste.

The mild, slightly nutty flavor of coral mushrooms makes them an excellent canvas for bolder ingredients. Pair them with aromatic herbs like thyme or garlic, or incorporate them into creamy sauces and risottos to enhance their natural earthiness. For a simple yet elegant dish, toss sautéed coral mushrooms with butter, lemon zest, and parsley, then serve as a side or garnish. Avoid overpowering them with heavy spices or long cooking times, as their delicate nature is easily lost.

One of the most critical steps in preparing coral mushrooms is proper cleaning. Their branching structure traps dirt and debris, so submerging them in water is not recommended, as it can waterlog their porous flesh. Instead, use a small brush or damp cloth to gently wipe away impurities. If necessary, trim any discolored or woody parts before cooking. This careful cleaning ensures their texture remains intact and their flavor untainted.

Foraging enthusiasts should exercise caution, as coral mushrooms have look-alikes, some of which are toxic. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert before harvesting. Once collected, store them in a paper bag in the refrigerator for up to 2 days to maintain freshness. When in doubt, purchase them from a trusted supplier to ensure safety and quality. With their unique appearance and versatility, coral mushrooms can elevate dishes from ordinary to extraordinary—provided they’re handled with care.

Frequently asked questions

No, not all coral mushrooms are edible. While some species, like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower coral mushroom), are safe to eat, others can be toxic or cause digestive issues. Always identify the specific species before consuming.

Edible coral mushrooms, such as *Ramaria botrytis*, typically have a cauliflower-like appearance, a mild odor, and a whitish to yellowish color. However, positive identification requires careful examination of features like spore color, habitat, and microscopic details. Consult a field guide or expert if unsure.

Some coral mushrooms are poisonous, such as *Ramaria formosa* (the pinkish coral mushroom), which can cause gastrointestinal distress. It’s crucial to avoid consuming any coral mushroom unless you are certain of its edibility.

No, coral mushrooms should not be eaten raw. Even edible species like *Ramaria botrytis* should be thoroughly cooked to improve digestibility and eliminate potential toxins or parasites. Always cook them before consumption.